As the public transportation operations remain restricted during Phase 1 of the general community quarantine (GCQ) on Monday, June 1, 2020, crowds of commuters were spotted waiting to catch their rides along Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City, despite the lack of mass testing needed to flatten the curve. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, these glaring scenes have already been prevalent throughout Metro Manila, which shows the daily struggle that commuters have to face.

Commuters are stranded along Commonwealth Avenue during the first day of the Metro Manila general community quarantine (Source: ABS-CBN News Facebook page https://bit.ly/3ckwPky)

As a commuter, I have occasionally experienced squeezing myself into congested buses, trains and jeepneys during rush hours, especially when I desperately needed to be on time for various scheduled events or activities. However, other commuters neither have the luxury of time nor money to choose less congested alternative routes or more comfortable rides, like Point-to-Point (P2P) Buses and Grab. This situation left them with no choice but to endure crowded rides to their destinations on a daily basis, prior to COVID-19.

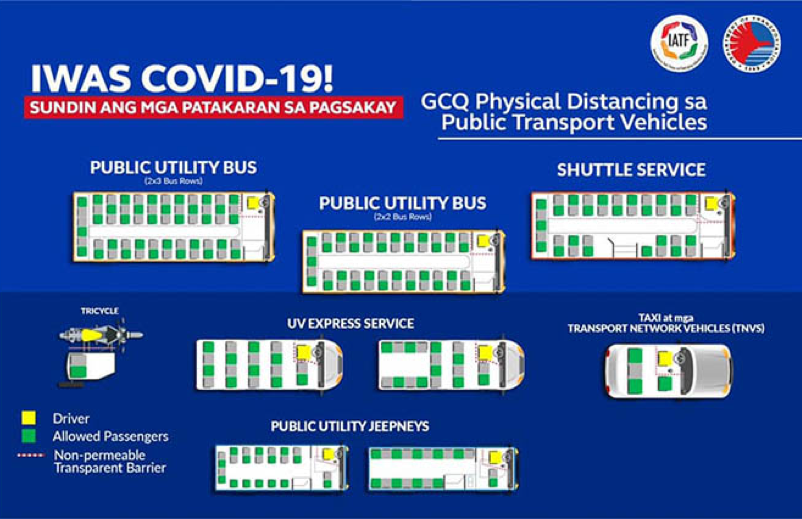

Public Transport Vehicles are required to operate with reduced passenger capacity, as part of the Inter-agency Task Force (IATF) physical distancing guidelines under the GCQ (Source: Department of Transportation – Philippines Facebook page shorturl.at/iwzDY)

However, in the new normal scheme, commuters are even more constrained with the strict physical distancing guidelines for public transport vehicles. Although vehicles will no longer be crowded, commuters still have to compete for the limited seats available, as they bear the struggle of long waiting times under the scorching heat or rainy weather. To make matters worse, limited seating capacity will also lessen the operators’ profits, which will make the transport service harder to sustain in the long run and further limit commuters’ mobility.

The experience of commuters forced to compete against each other shows the dehumanizing aspects of commuting. This experience points to an urgent need to uphold commuter rights to mobility by understanding these struggles as an issue of human dignity.

Reframing human dignity at the forefront of commuter rights begins with seeing commuters as human beings who are capable of making rational decisions. This entails treating commuter behavior as a natural response to the visible gaps within the current transportation system. Therefore, deviant (or ‘socially undesirable’) commuter behavior is not a product of a ‘lack of discipline,’ but a symptom resulting from dehumanizing conditions and limited transport supply unable to meet the overwhelming travel demand. Simply put, commuters are constrained by the choices that are available to them in their respective commutes.

Hence, this is why many commuters choose to wait in the middle of the road and cram themselves inside crowded public transport.

With that said, the role of dignity in commuting entails treating commuters as human beings whose mobility is tied to other fundamental necessities, such as balancing their needs to go to work punctually, spend quality time with their families and rest. After all, these are important needs that are consistent with the extensions of human dignity, in every person’s pursuit of authentic and holistic human development.

By reframing rights to mobility in this manner, commuting is no longer just about getting across two distinct points, but functions to support human needs. This framing adds a more human dimension to travel behavior that explains the constantly high travel demand among commuters.

At the end of the day, commuting is a human activity that should not pit commuters against each other, since everyone has a right to the dignified use of adequate and functional public transportation. However, the need for a dignified commute must not only be perceived as an economic problem, since commuters are human beings with intrinsic and inviolable human dignity.

Therefore, commuting must also include a social dimension, and transport planners and policy-makers must highlight its human aspects, by recognizing its mental, and emotional effects to commuters.

Written by Vince Nieva. Vince is a World Youth Alliance Asia Pacific (WYAAP) Official Trainer and currently works with AltMobility, a Philippine transport advocacy group.

Know more about how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected transportation in the Philippines by attending DignityInDepth. Sign-up at bit.ly/dignityforum